Military & Veterans News

Cover Story: A Most Senior Recruit: Top Heart Surgeon Joins the Army

Linda D. Kozaryn, American Forces Press Service

WASHINGTON -- After a career as a world-renowned, pioneer heart surgeon, 57-year-old William C. DeVries decided to serve in the Armed Forces.

The tall, lanky doctor, who implanted the first permanent artificial heart in Seattle dentist Barney Clark, signed on at Walter Reed Army Medical Center as a Defense Department contractor. He also joined the Army Reserve.

On December 29, 2000, DeVries was commissioned as a lieutenant colonel. On January 18, 2002, he became one of the oldest officers to graduate from the Army Medical Department Basic Officer course.

"The story goes back to when I was born at the Brooklyn Naval Hospital in 1943," Doc DeVries said in a recent interview. "My dad was a physician and surgeon on the destroyer USS Kalk. He was a lieutenant junior grade in the Naval Reserve.

"Right after I was born, he went to sea," he said. "Six months later, he was killed in the Battle of Hollandia in the South Pacific. Even though I never knew him, he's had a great impact on me all my life."

DeVries' mother, Cathryn, suffered a second loss shortly after learning of her husband's death. Her father, a World War I veteran, also died. "Can you imagine having a double funeral for your dad and your husband?" DeVries said. "All of a sudden, the family had no men in it, except for a little baby."

Grieving for the loss of the two men in her life, the single mother returned to her family in Salt Lake City, Utah. Six years later, she remarried and raised eight more children by her second husband, Don Nuttall.

Bottled-Up Emotions

"When I was growing up," DeVries said, "I noticed that I had a different last name from my brothers and sisters. But I had a great dad. He got me into Boy Scouting and all that stuff. I'd never ever even dream of calling him "stepfather.' He was my dad. But I knew that I had another dad that I didn't know much about."

Cathryn had essentially closed the door on the past. She never talked about her first husband. She was angry he'd been killed and angry he'd been buried at sea. She even refused to accept his medals awarded by the military.

DeVries was "a sole surviving son" in military terms, but he didn't know it until he tried to join the military during the Vietnam War. Although he was in college and getting ready to go to medical school, he said, he felt the patriotic thing to do was to join the Armed Forces.

"When the Cuban Missile Crisis happened, I was in a university and I saw people running and hiding from the service. It kind of made me sick,” he said, “because I really felt strongly that we have an obligation to serve our country.

"My father's death made it even more important. I felt that every generation must own its own liberties, its own freedoms."

But DeVries was not destined to serve his country – not then, anyway. As a sole surviving son, military officials said, he couldn't be put in an active theater. Because of an influx of draftees, they said, they didn't need him.

One officer told him that if he wanted to serve, he should come back after he got his medical degree. "I went back to school and did the best I could do," DeVries said of his next nine years.

The young doctor's subsequent medical career involved breakthroughs in modern medicine. In the early 1980s, he was instrumental in creating the artificial heart dubbed the Jarvik 7. From 1982 through 1987, he implanted the Jarvik 7 in four patients who collectively lived more than 1,300 days. In 1988, DeVries returned to traditional cardiovascular surgery until his retirement in 1999.

An Unexpected Dividend

The medical discovery paid an unexpected dividend. Publicity surrounding the artificial heart united DeVries with those who knew his father during World War II.

"At the time of the artificial heart implantation, my name and my picture were in just about every newspaper in the world," he said. "I started getting these strange letters from people like the president of a Florida bank, and from another guy in Portland, Oregon. They asked if I was related to Henry DeVries. I wrote back that I was."

Word spread among World War II veterans and the heart specialist started getting more letters, long letters, from his deceased father's shipmates. "They said things like he had a great tenor voice and his favorite song was "I Dream of Jeanie with the Light Brown Hair." He used to sing it in the shower and they all used to listen to him sing."

One man sent the Navy surgeon's medical books to the son. "It's unbelievable the things that people sent to me," DeVries said.

From the letters, he learned that his father had served as a chaplain as well as a surgeon. Henry was supposed to get off the ship at Hollandia, but when they arrived, his replacement hadn't shown up so he went back on board for the ship's next leg. His father's shipmates told the son they'd often told the doc to stay below deck, but he'd always come up to see what was going on. Henry was killed June 6, 1944, when Japanese aircraft attacked the ship.

"I must have had about 25 letters, and all of them had two things to tell me," DeVries said. "They said he died painlessly, and they said they got the pilot that killed him, that dropped the bomb on the ship."

Deeply Held Hostility

DeVries said he was amazed by the hostility the veterans still harbored toward their enemy. "These guys are now 85, 86 years old," he said. "I still get letters and they're still very angry about their enemy. I don't have any anger or hostility toward the Japanese people. But these soldiers really did. I kind of got a window into what their feelings were at that time."

This year, he plans to attend the veterans' reunion and meet some of the men who served with his father before it's too late.

"I never really knew much about him except for what I heard from these people," he said. "That part of the artificial heart project was the best part for me personally. Through all that interchange, I really began to know my father."

As DeVries pieced together stories about his father, his mother finally unveiled her memories. "One day my secretary said, "You've got a special, last patient of the day -- it's your mother,"" he said. "She sat down with me for about two hours in my office and told me about my father."

He learned that Henry DeVries came to America from Holland in 1924. Settling in Michigan, he became a naturalized citizen. He was an intern at a hospital in Salt Lake City when he met Cathryn, who was a nurse there.

"War broke out and all of his brothers joined up," DeVries said. "His dad … called up and said, "Henry, I'm embarrassed by you. The Germans have taken over our old country and here you are, an able-bodied American and you won't go and fight for your own country." He went down the next day and joined up."

The Missing Scrapbook

Forty-odd years after her husband's death, Cathryn gave her son a scrapbook he'd never seen before. It held a picture of the USS Kalk and a letter stating that Henry was killed in action. She also gave him his father's dog tags.

The book held a card with Cathryn's handwriting stating, "Hyacinth's a boy." Before their son was born, the couple had decided that if the baby were a girl, they'd name her Hyacinth. When the baby born December 19, 1943, turned out to be a boy, Cathryn sent the card to her husband. Henry was carrying the card on the day he died.

DeVries' ties to his father resurfaced again at a dinner he attended honoring the nation's outstanding high school students. DeVries was one of several guest speakers, as was a general from the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

DeVries mentioned his father's service and the general asked the doctor if he'd ever received his father's medals. Replying that he had not, the general offered to see if he could locate them.

"About four days later," DeVries said, "a guy comes to my office and he's got Dad's three medals -- the Asian Pacific Campaign Medal, the World War II Victory Medal, and the Purple Heart. Dad"s name was engraved on all of them.

"I said, "You keep these around?' and the guy said, "Your mother was notified, but she wouldn't accept them so we've had them in the files.'

Life-Altering Encounter

This is where the father-son story would have ended if DeVries hadn't gone golfing two years ago with Army Major General Evan Gaddis, then commander of the Army's recruiting command. The chance encounter changed the doctor's life.

"At the time, I was 56. I had a nice home near Fort Knox, Kentucky, and I was cutting back my practice," he said. "I was kind of disillusioned with medicine. Everybody was worried about their retirement plan, and the fun had gone out of it."

The general invited the heart specialist to accompany him to Washington, where he introduced DeVries to the commander at Walter Reed Army Medical Center. On the return flight, DeVries said, Gaddis made his pitch.

"He said, "It's a crying shame. Someone with your talent and your ability really could help the Army, but you're just learning how to play golf and wasting your time away writing papers and closing up your practice.'

"I started feeling guilty," DeVries said. "At that time, all this patriotism started sprouting in my chest and I realized I could do something."

In October, DeVries joined Walter Reed's Department of Surgery as a consultant. Still, Gaddis wasn't satisfied. The general told the doctor, "There's one more thing you need to do. You need to wear green."

Gaddis arranged for DeVries to join the Army Reserve. The general inspected him when he put on his dress uniform the first time, for his swearing-in ceremony at Fort Myer, Virginia. Standing in front of the mirror was an emotional moment, DeVries recalled.

"I am the most "waivered' person ever to wear an Army uniform," he said. "I had an age waiver and a health waiver. They went through all this stuff to make it happen. I didn't really appreciate it too much until I went to Officer Basic Course and it became a major deal. They didn't quite know how to handle me."

The 58-year-old trained alongside 21-year-old men and women. Overall, he said, he kept up. "The first week was all classroom stuff and they were pretty sharp," DeVries said. "But I knew a lot of the stuff."

The surgeon was impressed by how the military group congealed as a team.

"I've been on a lot of teams in my life, but I've never been on a team that was so close to each other," he said. "They took care of me and I took care of them. We did fine. I came out of there really feeling close, and still these people e-mail me all the time. I still talk to them about it."

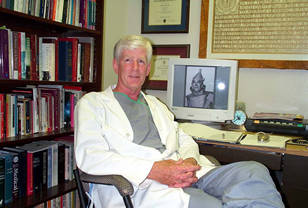

Back at Walter Reed, DeVries occasionally employs an unusual style in lectures to the medical center cadre. He dons a homemade Tin Man outfit, complete with a silver ax, to talk about the importance of the heart. Quoting the Wizard of Oz, he tells the young medical specialists, "Hearts will never be practical until they can be made unbreakable."

Along with his day job with the military, DeVries is assigned to the 324th Combat Support Hospital in Perrine, Florida, south of Miami, where he does Reserve drills about every other month. He supplements those drills with weekend duty in Washington. He plans to go to advanced officer training, and in February, he'll accompany his Reserve unit on a medical mission in Paraguay.

"I'm excited about coming to work in the morning and seeing all these young docs. Educating these residents is important. The quality of medicine here is just unbelievably good. I'm in the best position of my life right now -- doing fun things, exciting things, doing something for my country and my profession."

"I'm really proud of the fact that I'm serving," he added. "I've always felt that I had a military obligation. I think everybody has an obligation to serve. My obligation started at a late time, but I'll stay here as long as I can."

Since the war on terror began, Walter Reed has treated both U.S. service members and Northern Alliance soldiers wounded in Afghanistan.

"Every morning driving by Walter Reed's statue out there and seeing the flag flying on top of the hospital, it really means something to me," he said. "I feel like I'm just a small part of it, but I'm part of it."

SOURCE: American Forces Press Service via Veterans News and Information Service